Description

An interesting fact about note taking–during lectures, videos, or reading–is that it increases learning, even if the notes are never reviewed after being made. That’s because taking notes is an active process that involves

- Listening (or watching and listening) carefully to understand what is being presented

- Focusing attention on the subject

- Identifying the important and filtering out the less important

- Summarizing and paraphrasing the material, thus requiring a thoughtful interaction with it

- Engaging multiple cognitive channels (auditory as you listen and visual as you write)

- Using kinesthetic effort (writing or typing)

Of course, learning is enhanced even more if you do review your notes, and further still if you summarize or abstract them.

Notetaking Guidelines

Notetaking is something of an art, whether you are listening to a lecture, watching a video, observing a llive demonstration, or playing an audio file. The golden key is to take enough notes to capture the important points, including enough detail so that you can remember and understand them. If the notes are too skimpy, they won’t mean much when it comes time to review them. If all you do is copy the short bullets from a PowerPoint presentation or only the words and phrases the instructor writes on the board, you will likely be wracking your brain trying to decipher them later.

What do you make of these notes, for example:

Emergency prob solv

conceputalization delay

understand key

can’t act otherwise–stunned–deer headlights

At the opposite end, if you try to write down everything, you’ll be unable to understand what’s going on, having become a robot scribe, and you won’t get the gist or the details right. (There’s the possibly apocryphal story of a student who took notes so furiously that, when the professor started to tell a joke, the student wrote that down, too.

So here are some guidelines:

- Include important details, such as central ideas, conclusions, key ideas

- Write down what the presenter says when prefixed by an emphasis comment: “And most importantly,” “And note this,” “What really matters is” and so forth.

- Do not include more than a two or three examples (one is usually enough), off topic comments, rabbit trails (digressions), jokes, details you can easily look up (dates of important events, for example)

- Include process steps, cause and effect, before and after, or other sets of ideas that must go together to be meaningful

Use symbols to annotate your notes. Symbols allow quick notation either at the time you take the notes or when you review them. Here a just a few ideas:

- An asterisk * indicates an important thought

- An exclamation point ! indicates something provocative or controversial that you might disagree with

- An addition or plus sign + indicates that two or more ideas work together.

- An arrow –> indicates a cause and effect relationship or a time sequence (earlier and later)

How to Take Notes Using the Active Notes Sheets

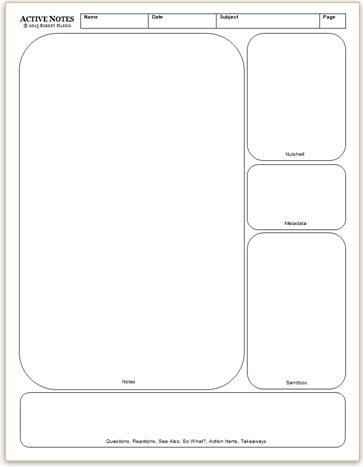

Available here is the Active Notes sheet (in PDF). This form has been designed to help you take better notes. Here is how to use it.

Infobar. Enter your name, the date, subject, and page number (if you have more than one page of notes for this subject).

Notes Area. Use this area to take your usual lecture notes or notes from a presentation or video. Use the guidelines above.

Nutshell. This box is for writing a summary, the very condensed ideas, significant implications, or the single, most important idea you want to remember when you return to these notes. In other words, six month or a year from now, when you are leafing through 100 pages of notes, glancing at the Nutshell of each one should tell you quickly what the notes are all about. Think of the Nutshell as a brief abstract of the session you made notes of. The Nutshell can also include an evaluation, as in “Excellent book, with several chapters on information overload.”

Metadata. Use this area to record bibliographic source informaiton (the name of the book you are taking notes from, the presenter’s name, the title of the video or PowerPoint presentation or speech, and so forth. You can also include the length of the presentation (was this a ten-minute chat or a three-hour lecture?).

Sandbox. The sandbox can be used for lecture or presentation related material, such as a graph, chart, diagram, mnemonic, contact information, and so forth. Second, it can be used for doodling and scribbling. Many people like to make little drawings or geometric shapes while they listen to a presentation or participate in a meeting. A third and most important use of the sandbox is to free up your working memory so that you can concentrate on the presentation, reading, or whatever. If, while you are listening to someone talk, you are constantly reminding yourself to pick up bread and milk afterwards, or to call Fred, or do something else, your working memory is so busy that you can’t effectively process what you’re supposed to be attending to. When you write down, “Pick up laundry,” you can release it from your mind and focus on the information.

Questions, Reactions, See Also, So What? Action Items, Takeaways. This panel is used for actively responding to the notes taken and the presentation or reading as a whole. The panel can be used to include:

- What questions do you still have? Questions that remain unanswered or that were generated by the presentation or your thinking about it.

- What is your overall reaction to the information? Is the argument plausible, ridiculous, convincing, and why?

- Who else has written or presented on this topic that you might want to look at? What other sources did the presenter or writer name that interest you?

- Now that you’ve heard or read alll this, so what? So What if the argumet is true? What are the implications?

- What are you going to do about it?

Students can also use this box to write a new summary or paraphrase of their notes when they study them. They leave the box blank when first taking their notes, and then down the road, such as studying for an exam, they fill it in, perhaps listing an item or two or three that absolutely must be remembered, or some steps in sequence. Writing something about the subject again further strengthens memory. And reviewing notes after some time has passed often suggests new ideas or conclusions that can be added here. Re-engaging notes by writing abstracts or paraphrases is a poweful learning aid, because it stimulates recall, produces active thought, and increases memory.

![]()

The worksheet should be viewed as a flexible tool, not as a constraint. Therefore, you are free to

- reassign purposes for any or all of these boxes.

- draw an arrow from any box to another to continue the first box’s function.

- turn the sheet sideways to provide a wide drawing area

- use the sideways orientation to write definitions in the Notes area and terms in the Questions, etc. area and then match them up as self assessment tool. (See Learning Strategy 7: Self Assessment, for more ideas on assessing yourself.)

- write questions in the Notes area, answers in the Nutshell, Metadata, and Sandbox area, and then fold the paper along the Notes / Nutshell-Metadata-Sandbox line (to hide theh answers). See how well you do and then check your work.

- be creative in the use of this sheet and its boxes. To coin a cliche, think outside the boxes.